Overview of the history of the classical guitar

The ancestors of the modern guitar, like numerous other chordophones, can be traced back through manifold instruments, and thousands of years, to ancient central Asia. Guitar-like instruments appear in ancient carvings and statues recovered from the old Persian capital of Susa. This would suggest that contemporary Iranian instruments such as the tanbur and setar are distant cousins of the European guitar, as they all derive ultimately from the same ancient origins, but by very different historical routes and influences.

Historians are not all in agreement as to how the instrument that would become the modern classical guitar found its way to Europe, but we do know that in the Early Middle Ages, instruments with three or four strings called 'guitars', were present on the Iberian Peninsula. An impressive variety of stringed instruments appear in the illustrations that accompany the Cantigas de Santa Maria (426 songs devoted to the Virgen Mary), which were written in the 13th century during the reign of Alfonso the Wise of Spain. These miniatures are a primary source of information as to which instruments were used to perform these songs, and include paintings of two instruments that share some characteristics with the modern-day guitar: the Latin guitar and the Moorish guitar.

The construction and tuning of these two medieval instruments were different to that of the modern guitar, however. The Latin guitar, or Guitarra Latina, possibly descended from the cithara, an instrument introduced by the Romans during their colonization of Hispania (218 BC-5th century). This guitar had a narrow neck, curved sides, four sets of double strings and a single hole. The Moorish guitar, or Guitarra Morisca, was brought to Spain by the Moors during their occupation of Al-Andalus (711-1492), as they called the territory that is now Spain, or was an adaptation of the Latin Guitar. In fact, it looked a little bit like something between a Latin guitar and a lute and had a wider fingerboard than the Latin guitar, an oval soundbox and many sound holes on its soundboard.

It seems possible that a process similar to a ‘natural selection’ of chordophones took place on the Iberian Peninsula during the 14th and 15th centuries: some instruments died out, whilst others adapted and changed as they became more popular. By the 16th century, two instruments had evolved that were clearly precursors of the instrument we know as the guitar today. These were the vihuela de mano and the four-course guitar.

The vihuela had six or sometimes even seven double courses of strings and was built like a large guitar. It was the favoured instrument of the ‘cultured’: royal musicians played Renaissance music on the vihuela to the noblemen and noblewomen at court. The vihuela was also very popular in Italy, possibly because Naples and Sicily were under the Spanish rule of the House of Aragon.

The four-course guitar, in contrast, was played by the common people in the town and countryside, for strumming the chords of popular songs. It was also a much smaller instrument than the vihuela. It had ten frets and the strings of this instrument (three double courses and one single, at the top) were tuned C-F-A-D, which corresponded to the centre four courses of the vihuela. It was popular all over Europe.

During the next three centuries several important changes occurred in the evolution of the guitar. In the Baroque period, a fifth double string was added to the four-course guitar. Called the five-course vihuela or five-course guitar, it supplanted both the vihuela and four-course guitar to become the most popular instrument of the time. One of the reasons why it was so well received was that it was much simpler to play Baroque music than Renaissance music, and resulted in a huge increase in the number of guitar players across the European continent. In Italy and France, this Baroque instrument was known as a chitarra spagnuola.

The first treatise to the ‘Spanish guitar’ appeared in 1596 with the publication of Guitarra Española de cinco órdenes (Five-Course Spanish Guitar), written by Juan Carlos Amat. A doctor by trade, Amat was also a guitar aficionado, and his book, described in nine chapters how to string, tune and strum the chords of a five-course guitar. It became an early modern-era best-seller.

By the end of the 18th century, the Spanish guitar had acquired a sixth string and the double courses of strings had been replaced by single strings: E-A-D-G-B-E. The change from double to single strings was the result of the invention of metal bass strings which had more volume than traditional gut strings. Although there was some resistance among guitar players to this new form of string, the manufacture of instruments with double strings gradually became obsolete.

During the 19th century the Spanish master luthier and guitarist Antonio Torres Jurado gave the contemporary classical guitar its definitive form. Known as the ‘father’ of the modern guitar, Torres increased the size of the instrument, made the soundboard thinner and lighter, and perfected an internal bracing system in the form of a fan that improved the strength of the instrument as well as the distribution of the sound waves. He also invented the ‘Spanish heel’, whereby the neck and headblock are carved from one piece of wood, and a part of the neck remains inside the body of the guitar when the instrument is assembled. Torres is also credited with the development of the classical guitar’s first cousin, the flamenco guitar.

In the 20th century, the contribution of Spanish virtuoso Andres Segovia to the history of the guitar cannot be over emphasized. He legitimized the Spanish guitar by separating it from its reputation of being a folkloric instrument fit only for playing in cafes and bars and introducing it to a global audience; Segovia secured the future of this magnificent instrument by proving it was worthy of the most renowned concert halls all over the world.

Antonio Torres Jurado, the inventor of the modern classical guitar

Antonio de Torres Jurado (1817-1892) is considered the Stradivari of the Spanish classical and flamenco guitars. Born in the province of Almeria in the south of Spain, Torres served an apprenticeship with a carpenter in Vera between the ages of 12 and 18, where he was initiated into the craft of working with wood.

Torres married his first wife in 1835, but the couple suffered severe economic difficulties, as well as the death of three of their four children. When his wife succumbed to tuberculosis in 1845, Torres moved first to Granada for a few months, where he was introduced to the art of guitar-making by luthier José Pernas, then on to Seville where he opened his own guitar shop.

Torres’ association with the eminent guitarist and composer Julián Arcas was particularly important to his career. Arcas encouraged him to branch out from simply selling guitars to building his own models, and appealed to him to find a way of improving the sonority of the instrument, which had a limited volume at the time: Torres was more than up for the challenge. He constructed a more powerful instrument by upping the size of his guitars to 65cm and raising the fingerboard.

Torres went on to built around 320 guitars in two separate epochs: 1852-1869 and 1875-1892. The first period corresponds to his years in Seville and were characterized by a time of experimentation, where he applied his significant imagination and trial and error to gradually improve the volume and sustain of his instruments. In 1856 his patience was rewarded: it was the year he completed his famous Leona (Lioness) model using innovative construction techniques such as the internal fan-bracing below the soundhole and incorporation of the Spanish heel. The Leona would serve as a model for all of his later guitars.

This first epoch was Torres’ most prolific. Seville was a buzzing centre of economic activity at the time, and he could find all of the precious woods he needed to build his most valuable guitars. Many of the most famous guitarists of the time became his clients, including Francisco Tarrega and Miguel Llobet. In 1858 Torres achieved fame in the world of guitar making when he was awarded the bronze medal for an exquisitely decorated instrument in birdseye maple at the Seville Exhibition of that same year. During this period he also met and married his second wife with whom he went on to have four children.

However, Spain was soon to enter into an economic depression which would change the course of the master luthier’s life. Torres was eventually forced to abandon his workshop in Seville for Almeria once more, where he opened a china shop, as well as a luthier’s workshop to try and make ends meet. He combined his work in the shop with guitar making until his death there in 1892. In this second epoch, due to his fame, his guitars were very much in demand, although the instruments he made at this time were mostly basic models for local players. Throughout his lifetime, he never really became free from poverty.

His legacy lived on, however. The guitars Torres designed and made were such superior instruments to those constructed up until that time, that they changed the way guitars were built for ever. By modern standards, they wouldn’t be considered particularly loud, but they had a clear, balanced sound with a distinct character, a richness of timbre and wonderful projection.

Although there are some differences between Torres' classical guitars and the instrument we know today, the vast majority of contemporary classical guitars are still quite close in design to the formula Torres perfected some 150 years ago. Most guitar makers still incorporate some version of the fan-bracing that Torres refined, as well as the Spanish heel. Luthiers experiment with different woods today, however. Torres' made his soundboards with European spruce (Picea abies), whereas contemporary luthiers largely use Western red cedar (Thuja plicata). Torres' also used strings made of gut for the trebles and silk for the basses, overwound with silver. Since the 1950s most classical guitars have nylon strings.

Torres died in Almeria in November 1892. In 2013 the Museum of the Spanish Guitar Antonio Torres was inaugurated in the city of his birth.

What is the traditional spanish system?

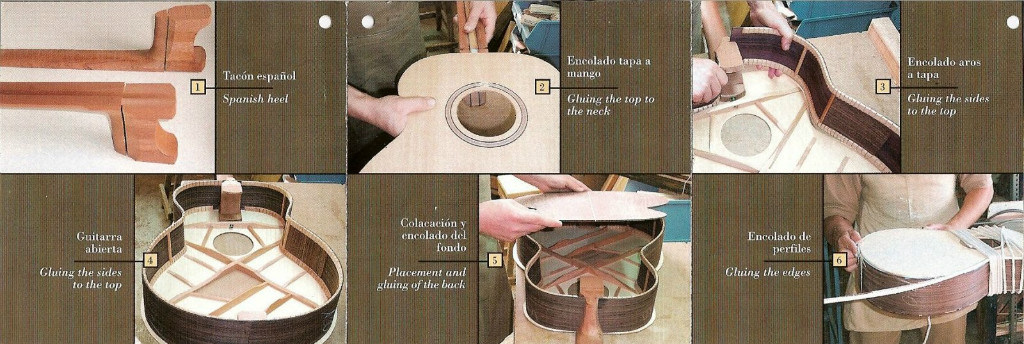

It is a system of guitar making, that is characteristic in Spain and which is applied to all Spanish guitars that are made here. Using this method, part of the guitar neck remains inside the body when the guitar is assembled, creating the “Spanish heel”.

Why a guitar made with the traditional spanish system?

This system guarantees a better construction of the classical guitar and the flamenco guitar than those that use a joining system to attach the neck to the body, like making a piece of furniture. Apart from the sonic advantages, it offers a far better stability and durability of the instrument.

The "Spanish heel" is a construction feature most commonly associated with Spanish-made classical guitars. In this style of construction, the neck and the headlock are sculpted from the same piece of wood , and the body is built around the neck. The result is a very solid neck mounting, because the entire body is built around the end of the neck. Indeed, it is the ideal method of construction.